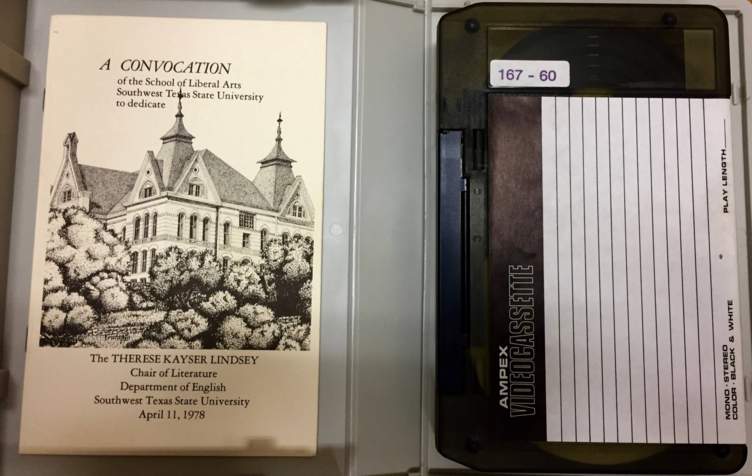

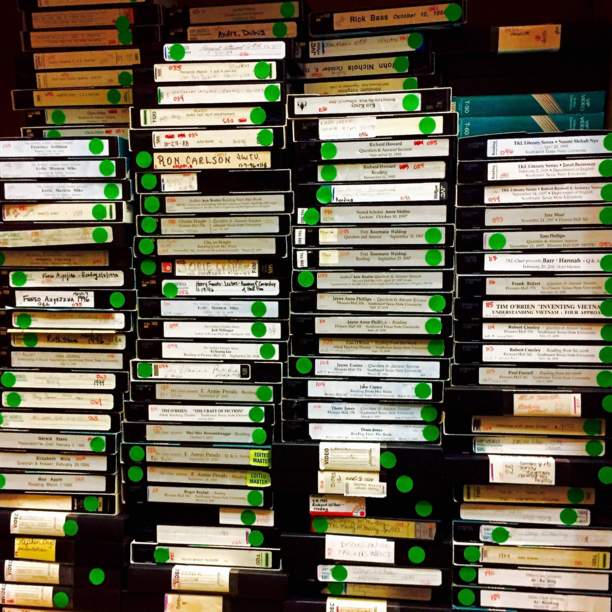

In a locked closet, in another locked and little-used room in the English Department at Texas State University, lay hundreds of dusty and nearly disintegrating VHS tapes and DVDs. These recordings, however, weren’t just old home movies of picnics and fundraisers, but constitute perhaps one of the most significant archives in the literary world, a collection now valued well north of $1 million dollars. Until 2005, the tapes had been stacked on shelves, filed away and forgotten, some for nearly 30 years, and they were just awaiting the digital era for their re-discovery.

Originally entitled the Therese Kayser Lindsey Readings Series, visiting writers have come to campus to deliver lectures, read from their work, hold Q&A’s with graduate students, and host workshops at the Katherine Anne Porter House. Previously, each event has been filmed and shared with English Department faculty for their research and teaching purposes. Now, preserved digitally for the first time, these recordings have been re-mastered, archived, and made available to the public in a way none of the original organizers and participants could’ve imagined.

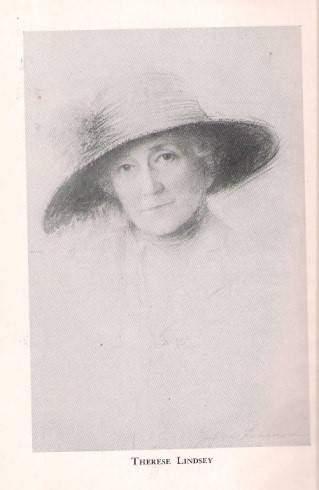

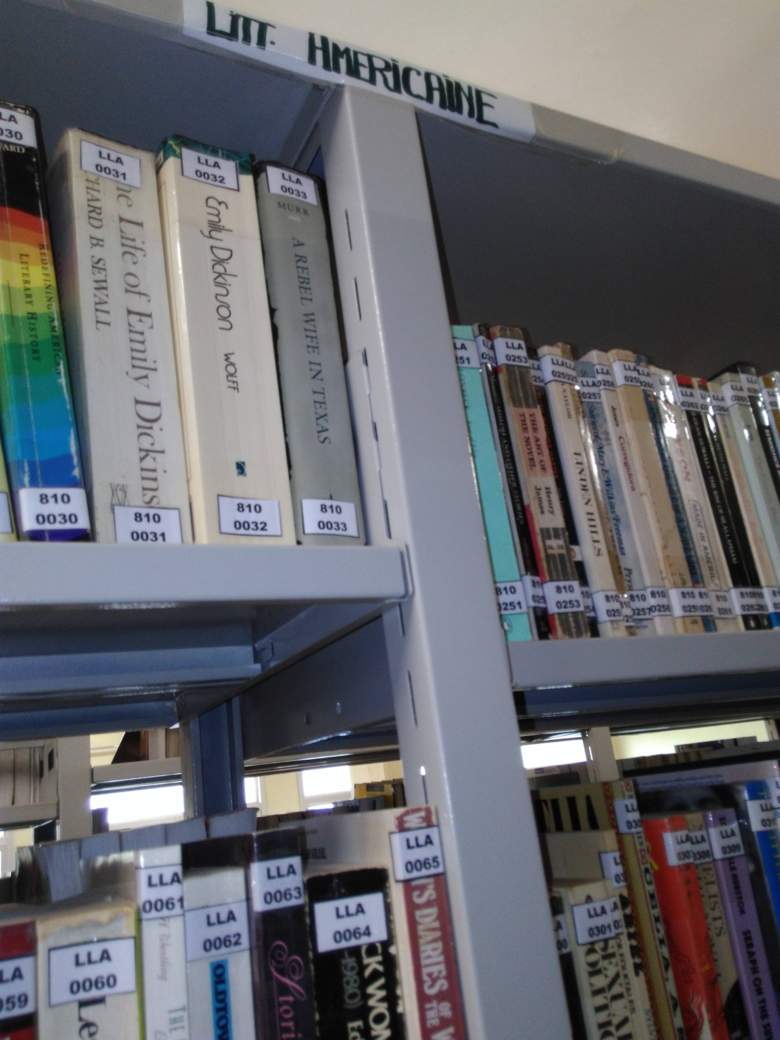

Begun in 1978, almost exactly 40 years ago, Louise Lindsey Merrick created the series as a living memorial to her mother, Therese Kayser Lindsey, a Texas writer born in 1870 in Chappell Hill, one of the many scrub-grass towns that dot the hill country between Austin and Houston. Lindsey was a poet, newspaper writer, and producer of operas, known for a narrative poem about the 1900 Galveston Hurricane’s destruction. Lindsey graduated from Texas State University in 1905, and throughout her life, invested heavily in the future of literature in Texas, establishing the Poetry Society of Texas in 1921. Mrs. Lindsey was a resident of Tyler, TX until her death in 1957.

The first event was entitled “The American Southwest: Cradle of Literary Art” and featured Larry McMurtry, John Graves, R.G.Vliet, and Lon Tinkle. In the early 80’s, the series expanded to feature other Texas and notable southwest writers like Bill Wittliff, James Dickey, and Thomas Berger. As the series continued growing in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, the department brought many titans of the literary world, authors such as Allen Ginsberg, Margaret Atwood, Ken Kesey, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Sandra Cisneros.

Despite the obstacles, the department arranged for each event to be filmed. Recently retired Professor Nancy Grayson, the TKL coordinator from 1983-1986, helped make the reading series an institution at Texas State and fought to get each event recorded, no small feat given the cumbersome recording equipment of the analogue era.

“The goal,” Grayson said in an email, “was to ensure that as many students and faculty as possible heard our speakers and to give them the opportunity to hear and experience Q&As with great literary artists…. Obviously, filming has enlarged audiences extensively by continuing to provide access to the presentations down through the years.”

Fast-forward again to 2005 and the tapes in the Brasher closet and Tom Grimes, then the Director of the MFA in Writing Program, when he “rediscovered” the tapes. Professor Grimes imagined what few others could: a digital home for these events, where anyone in the world could, with a touch of a button, hit “Play,” and beam some of the world’s foremost authors into their living rooms, where viewers could watch them read, hear them answer questions, and marvel at humanity’s urge to tell stories. Given the nascency of the Internet and digital-streaming services at the beginning of this century, Grimes’s foresight also cannot be understated. He knew this was an important resource for the university and that’s why he’s “pushed so hard to get these videos online,” he said.

Still, given the technological, professional, and contractual limitations, it would take another decade to realize this concept. The archive currently stands just shy of 500 events, or nearly one terabyte of data, and grows every year. This information needs a secure location with regular backups and high-speed servers for hosting streaming content. Another battle has been the lack of technical expertise in developing the website and video-player interface, two subjects largely beyond the department’s knowledge.

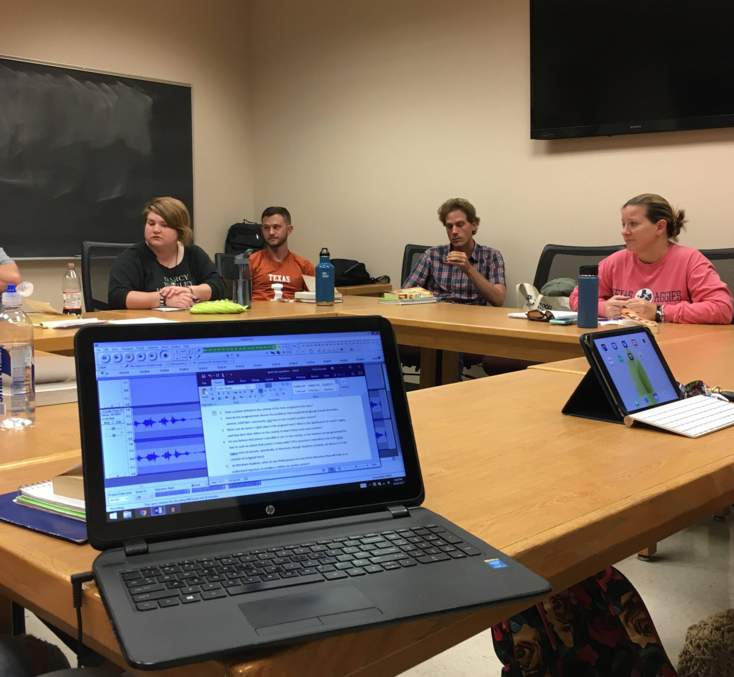

In 2014, the English Department paired with the Learning Application Solutions component of the office of Instructional Technologies Solutions. With the help of ITS, the department secured the necessary server and bandwidth space and helped finish the re-mastering process, where additional graduate students converted all of the DVD files into high-quality MPEG-4 files better suited for adaptive bitrate streaming.

With an estimated 95% percent of the files online, the department begins to focus on the second stage of development. They’re in the beta-testing stages of a new portal interface that will allow for an improved user experience, one of the biggest shortcomings so far. This new portal will offer more intuitive content hierarchy, improved search capabilities, and eventually transcript files.

“The focus now,” said English Department Chair Dr. Dan Lochman, “is to make these videos accessible to scholars and academia.” However, in the future, they plan to group these talks, readings, and Q&A’s into learning modules, organized by creative writing craft elements and techniques. The hope is that these adaptable learning modules will expand awareness and access to “develop lesson plans for everyone, not just within academia,” Lochman said.

Yet, challenges lie ahead. Closed Captioning and ADA compliance and slow-streaming speeds are several of the problems viewers encounter. Additionally, many of the events from the first two decades either never had a permanent copy stored or weren’t ever filmed, and so are likely lost forever.

But there’s little doubt the archives will continue to grow in ways that we can’t even begin to imagine, because these events and their recordings bridge a divide in the writer-reader relationship. Authors can seem remote, almost superhuman when hidden behind their words, but seeing them read and speak about their work allows anyone a glimpse at the wizard pulling the strings. This act of connection in an otherwise solitary experience, perhaps, represents something new in the literary world, as one can imagine other closets, at other universities, that also possess hidden gems awaiting their own re-discovery for the digital age.

If nothing else, as Professor Grimes said, the Lindsey Archives hope to “give everyone, everywhere, online access to one of the richest — if not the richest — literary video archives in the country.”

More information:

The collection is housed via the English Department’s graduate-run literary magazine, Front Porch Journal.

For a list of this year’s writers and events: The Katherine Anne Porter Center and The Wittliff Collections.

For a more in-depth biography of Therese Kayser Lindsey see the book Texas Women Writers: A Tradition of Their Own.

Written by Eric Blankenburg with reporting by Gloria Russell

San Marcos, TX

San Marcos, TX

On October 28, The Austin office of the Irish Consulate hosted students from the 2016 Texas State in Ireland program for a reception and conversation on their five-week stay in Ireland this past summer. Consul General Adrian Farrell encouraged the students to share their impressions of Ireland, noting the growing cooperation between the Republic of Ireland and the Austin area, as well as the long history of the Irish in Texas and the southwest. Consul Farrell and the students were joined at the reception by Dr. Ryan Buck, Texas State’s Assistant Vice President for International Affairs. The Texas State in Ireland program, directed by English Department faculty members Nancy and Steve Wilson, has taken Texas State students to Cork, Ireland each summer since 1999, allowing more than 300 of them to explore a vibrant country that was home to the ancestors of millions of Americans. While in Ireland, the students from the 2016 program visited such cultural sites as Dublin; medieval Ross Castle, in Killarney; 10th-century Celtic settlements on the Dingle Peninsula; Gougane Barra Forest Park, in the Shehy Mountains of County Cork; and Great Blasket Island, a rugged outpost off the western coast. They also earned six hours of credit for completing advanced English courses in Travel Writing and Irish Literature. Steve Wilson noted at the reception that the program offers students the opportunity to be much more than travelers. They are encouraged to investigate the country and its people, discovering common ground with the Irish but also the important ways peoples of different cultures interact with and understand their world.

On October 28, The Austin office of the Irish Consulate hosted students from the 2016 Texas State in Ireland program for a reception and conversation on their five-week stay in Ireland this past summer. Consul General Adrian Farrell encouraged the students to share their impressions of Ireland, noting the growing cooperation between the Republic of Ireland and the Austin area, as well as the long history of the Irish in Texas and the southwest. Consul Farrell and the students were joined at the reception by Dr. Ryan Buck, Texas State’s Assistant Vice President for International Affairs. The Texas State in Ireland program, directed by English Department faculty members Nancy and Steve Wilson, has taken Texas State students to Cork, Ireland each summer since 1999, allowing more than 300 of them to explore a vibrant country that was home to the ancestors of millions of Americans. While in Ireland, the students from the 2016 program visited such cultural sites as Dublin; medieval Ross Castle, in Killarney; 10th-century Celtic settlements on the Dingle Peninsula; Gougane Barra Forest Park, in the Shehy Mountains of County Cork; and Great Blasket Island, a rugged outpost off the western coast. They also earned six hours of credit for completing advanced English courses in Travel Writing and Irish Literature. Steve Wilson noted at the reception that the program offers students the opportunity to be much more than travelers. They are encouraged to investigate the country and its people, discovering common ground with the Irish but also the important ways peoples of different cultures interact with and understand their world.