If you counted the number of people in prison in Texas for drug possession, you would have a population roughly the size of the student body at Texas State University. If you included other non-violent offenders, this number spikes to over 100,000, much larger than the population of San Marcos. Numbers like these suggest that crime, justice, and prison reform should rank high on topics of discussion in our classrooms. The university’s Common Experience is a way to explore these issues.

If you counted the number of people in prison in Texas for drug possession, you would have a population roughly the size of the student body at Texas State University. If you included other non-violent offenders, this number spikes to over 100,000, much larger than the population of San Marcos. Numbers like these suggest that crime, justice, and prison reform should rank high on topics of discussion in our classrooms. The university’s Common Experience is a way to explore these issues.Each year, the university selects a theme as its yearlong initiative to cultivate a common intellectual conversation. Designed to enhance student participation and foster a sense of community, the Common Experience brings students together to read and engage with books and other works of art, to listen to visiting speakers, and to engage in classroom discussions in order to explore issues in our society. This year, the Common Experience theme highlights issues such as racial disparity in sentencing and the war on drugs, among other problems in our justice system.

Professor Steve Wilson’s graduate course, “Literature and the Criminal Mind,” provides a model for tackling similar issues in this year’s Common Experience. Professor Wilson’s course offers students the opportunity to read literature through the lens of criminal narrators and their experiences in the justice system. As the course description on his course syllabus suggests, “The goal is to explore the various ways in which texts portray the criminal mind.” While reading novels such as Junky by William S. Burroughs and Pimp by Iceberg Slim, students examine topics such as guilt, psychology and crime, social attitudes toward crime and criminals, redemption, “fugitive” language (as Burroughs phrases it) and punishment.

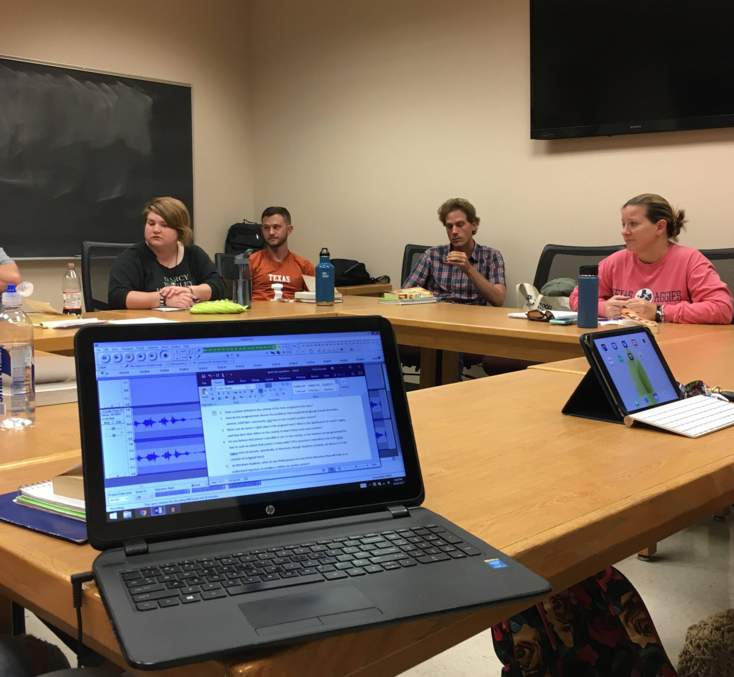

To get an understanding of how this course relates to this year’s Common Experience theme, I visited one of their discussions. On a muggy October night in Flowers Hall, the students explored ways that literature can bridge the gap between “criminals” and society.

“People are capable of incredible empathy, and literature helps us connect with each other,” Patrick Funderburg said. As the students’ discussion demonstrated, reading texts sympathetic to people unlike them forced them to wrestle with conceptions of right and wrong. This invariably led to questions of justice and fairness in the criminal system. “Criminals can absolutely become a victim of the justice system,” said Eden Jasuta, turning the discussion toward systemic inequalities of racial bias that occurs in all stages of the penal system. But when asked if these texts offer solutions, John McClellan shook his head: “The best literature doesn’t answer questions; it asks them,” he argued.

As the Common Theme and students in Professor Wilson’s class illustrate, it’s one thing to identify the problem, but it’s another thing entirely to find solutions. While the humanizing power of literature can help readers develop a more complex understanding of criminals, a compelling narrative still can’t solve the primary focus of this year’s Common Experience theme: the problem of mass incarceration in America. But as this student-led discussion suggests, complicating one’s conception of what it takes to commit a crime can go a long way in overturning previously held biases and prejudices. This suggests that a first step in addressing our overcrowded prisons is to read stories about the people inside, and read them not as outsiders, but as the criminals themselves see it.

To illustrate this idea, Katharine Kistler used the example of a drug addict. “People say drug addiction is the addict’s choice, but it’s more complicated,” she said while reflecting on Junky, Burroughs’s fictionalized account of using and peddling heroin in the 1950s and its similarity to the War on Drugs. Lisa Magnusson agreed with her, adding, “People get out of prison and go right back out to scratch that itch.”

Unfortunately, the numbers support this claim. Possession and drug-related charges are one of the more common ways people end up with a felony. Compounding the problem, a majority of prisoners suffer from some form of substance abuse, but only 11% receive treatment while incarcerated, according to the Center on Addiction.

In addition to addiction and justice, the class and the Common Experience explore what happens after the offender has paid their debt to society. Regardless of the nature of the crime, a felony conviction will remain on a person’s record forever. With today’s availability of Internet databases, employers can dig into every candidate’s background and often pass on those with a record. This action can hamper the ex-convict’s search for housing and government benefits such as food stamps. As Tyler Newlin argued, “A felony nowadays is a life sentence.”

While these students may not ever have answers to the questions this year’s Common Theme asks them to consider, the number of people in prison for drug possession proves that the need for critically thinking students grows in relation to the prison population. One day, these students might have power to change the system. Ultimately, the idea that having difficult conversations may empower them to improve the world is an idea that lies at the heart of our democracy, and it’s the goal of a humanities education.

–Gloria Russell, English major